?>

?>

Over 4 Million Copies Sold

The revolutionary strategy still shaking up the world of marketing

The idea for positioning came from a young unknown advertising guy named Al Ries who had his own agency Ries, Cappiello, Colwell in New York City back in the Mad Men era of the 1960’s. Al’s original idea was called the “rock.” Every brand needed a solid rock to differentiate itself from all the other brands in the category.

But not any rock. The “rock” had to be a word or concept that would be instantly accepted by prospects, like The leading toothpaste.

Al discussed the idea with the guys at the agency. One of his account executives, Jack Trout, suggested calling the rock a “position” instead. Al agreed. Al’s rock idea became positioning and it would change the world of marketing.

But not right away. The idea never went anywhere until 1972, when Al’s speech on positioning at the Sales Executives Club of New York got the attention of Rance Crain, editor of Advertising Age.

Rance Crain, Editor of Advertising Age

Rance suggested the topic of positioning would make a good series of articles for his magazine. Al, of course, agreed. The legendary three-part series of articles on positioning by Al Ries & Jack Trout was printed in April and May, 1972 – The Positioning Era Cometh.

Over the next few months, hundreds of articles on the pros and cons of positioning were written. From David Ogilvy on down, everybody had an opinion on positioning. In the end, positioning won out and companies in particular sang its praises.

A major highlight was when the positioning idea was featured on the front page of The Wall Street Journal. The article was not all that favorable, but it didn’t matter. Positioning was here to stay.

Positioning remained popular. Over the next decade, 150,000 reprints of the original Ad Age articles were given away by the agency. Then the now-infamous book was finally published.

Positioning: The Battle for Your Mind by Al Ries & Jack Trout was published by McGraw-Hill in 1981. It has become one of the most famous and best-selling marketing books of all time. It has sold more than two million copies around the world and has been translated into over 20 languages.

In 2001, a 20th-anniversary edition was published with comments from the authors. Al Ries was very proud to see the book republished however, disliked the cover, especially that the word “battle” was in red instead of “mind.” The most important thing to remember about positioning is that it takes place in the MIND, not the MARKETPLACE.

In 2009, Advertising Age magazine asked its readers what the best book on marketing they ever read was.

Positioning was #1. Coming in at #3 was another Ries book The 22 Immutable Laws of Branding written with his daughter Laura Ries.

Positioning was also named one of the most important ideas of the last 75 years.

Readers of Advertising Age voted Positioning the best book on marketing they ever read, 2009.

Here is the original text from the Advertising Age articles. The birth of the Positioning movement.

By Al Ries and Jack Trout

Reprinted from Advertising Age 1972

Today it has become obvious that advertising is entering a new era. An era where creativity is no longer the key to success.

The fun and games of the ‘60s have given way to the harsh realities of the ‘70s. Today’s marketplace is no longer responsive to the kind of advertising that worked in the past. There are just too many products, too many companies, too much marketing “noise.”

To succeed in our over-communicated society, a company must create a “position” in the prospect’s mind. A position that takes into consideration not only its own strength and weaknesses, but those of its competitors as well.

Advertising is entering an era where strategy is king.

If you had to pick an official date to mark the end of the last advertising era and the start of the new one, your choice would have to be Wednesday, April 7, 1971. In the New York Times that day was a full-page ad that seemed to generate very little excitement in the advertising community.

But then, an abrupt change in the direction of an industry isn’t always accompanied by the blowing of bugles. You sometimes need the vantage point of history to realize what has happened.

The ad that appeared that spring morning in 1971 was written by David Ogilvy. And it’s no coincidence that the architect of one era called the tune for the next.

In the ad, the articulate Mr. Ogilvy outlined his 38 points for creating “advertising that sells.” In the first place on his list was a point Mr. Ogilvy called “the most important decision.” Then he went on to say, “The results of your campaign depend less on how we write your advertising than on how your product is positioned.”

Blow the bugles, the positioning era has begun.

Five days later, in the New York Times and in Advertising Age, another ad appeared that confirmed the fact that the advertising industry was indeed changing direction. Placed by Rosenfeld, Sirowitz & Lawson, the ad listed the agency’s four guiding principles.

In first place was, you guessed it. According to Ron Rosenfeld, Len Sirowitz and Tom Lawson, “Accurate positioning is the most important step in effective selling.”

Suddenly the word and the concept was in everybody’s ads and on everybody’s lips. Hardly an issue of Advertising Age passes without some reference to “positioning.”

In spite of Madison Ave.’s current love affair with positioning, the concept had a more humble beginning.

In 1969, we wrote an article entitled “Positioning is a game people play in today’s me-too marketplace,” which appeared in the June, 1969, issue of Industrial Marketing. The article made predictions and named names, all based on the “rules” of a game called positioning.

One prediction, in particular, turned out to be strikingly accurate. As far as RCA and computers were concerned, “a company has no hope to make progress head-on against the position that IBM has established.”

The operative word, of course, is “head-on.” And while it’s possible to compete successfully with a market leader (the article suggested several approaches), the rules of positioning say it can’t be done “head-on.”

Three years ago this raised a few eyebrows. Who were we to say that powerful, multibillion-dollar companies couldn’t find happiness in the computer business if they so desired?

Desire, alas, was not enough. Not only RCA, but also General Electric, bit the IBM dust.

With two major computer manufacturers folding one right after another, the urge to say, “I told you so,” was irresistible.

Last November, a follow-up article, “Positioning revisited: Why didn’t GE and RCA listen?” appeared in the same publication.

As GE and RCA found out, advertising doesn’t work anymore. At least, not like it used to. One reason may be the noise level in the communications jungle.

The per-capita consumption of advertising in the U.S. is approaching $100 a year. And while no one doubts the advertiser’s financial ability to dish it out, there’s some question about the consumer’s mental ability to take it all in.

Each day, thousands of messages compete for a share of the prospect’s mind. And, make no mistake about it, the mind is the battleground. Between six inches of grey matter is where the advertising war takes place. And the battle is rough, with no holds barred and no quarter given.

The new ballgame can prove unsettling to companies that grew up in an era where any regular advertising was likely to bring success. This is why you see a mature, sophisticated company like Bristol-Myers run through millions of dollars trying to launch me-too products against strongly dug-in competition. (If you haven’t noticed, Fact, Vote and Resolve are no longer with us.)

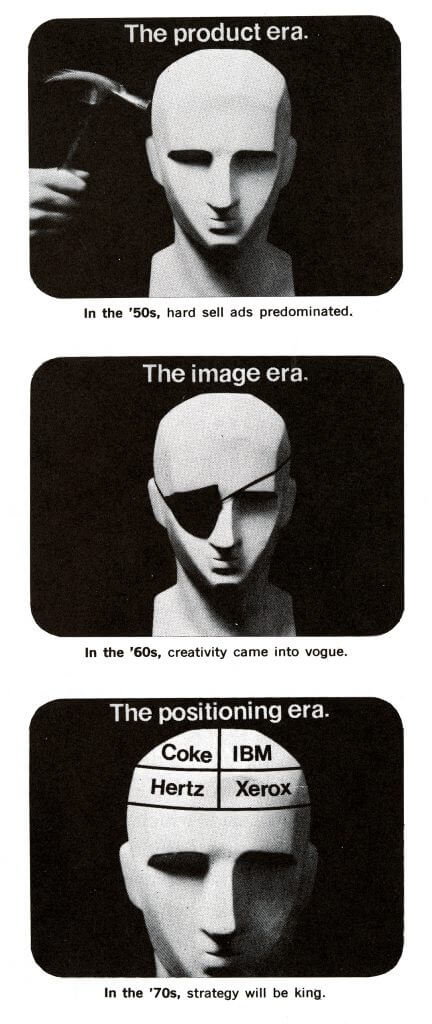

To understand why some companies have trouble playing in today’s positioning game, it might be helpful to take a look at recent communications history.

Back in the ‘50s, advertising was in the “product” era. In a lot of ways, these were the good old days when the “better mousetrap” and some money to promote it were all you needed.

It was a time when advertising people focused their attention on product features and customer benefits. They looked for, as Rosser Reeves called it, the “Unique Selling Proposition.”

But in the late ‘50s, technology started to rear it ugly head. It became more and more difficult to establish the “USP.”

The end of the product era came with an avalanche of “me-too” products that descended on the market. Your “better mousetrap” was quickly followed by two more just like it. Both claiming to be better than the first one.

The competition was fierce and not always totally honest. It got so bad that one product manager was overheard to say, “Wouldn’t you know it. Last year we had nothing to say, so we put ‘new and improved’ on the package. This year the research people came up with a real improvement, and we don’t know what to say.”

The next phase was the image era. In the ‘60s, successful companies found their reputation or “image” was more important in selling a product than any specific product feature.

The architect of the image era was David Ogilvy. As he said in his famous speech on the subject, “Every advertisement is a long-term investment in the image of a brand.” And he proved the validity of his ideas with programs for Hathaway shirts, Rolls-Royce, Schweppes and others.

But just as the “me-too” products killed the product era, the “me-too” companies killed the image era. As every company tried to establish a reputation for itself, the noise level became so high that relatively few companies succeeded. And most of the ones that made it did it primarily with spectacular technical achievements, not spectacular advertising.

But while it lasted, the exciting, go-go years of the middle ‘60s were like a marketing orgy.

At the party, it was “everyone into the pool.” Little thought was given to failure. With the magic of money and enough bright people, a company felt that any marketing program would succeed.

The wreckage is still washing up on the beach. Du Pont’s Corfam, Gablinger’s beer, Handy Andy all-purpose cleaner, Look magazine.

The world will never be the same again and neither will the advertising business. For today we are entering an era that recognizes both the importance of the product and the importance of the company image, but more than anything else stresses the need to create a “position” in the prospect’s mind.

The great copywriters of yesterday, who have gone to that big agency in the sky, would die all over again if they saw some of the campaigns currently running (successful campaigns, we might add).

Take beer advertising. In the past, a beer copywriter looked closely at the product to find his copy platform. And he found “real-draft” Piels, and “cold-brewed” Ballantine. Back a little farther he discovered the “land of the sky blue waters” and “just a kiss of the hops.”

In the positioning era, however, effective beer advertising is taking a different tack. “First class is Michelob” positioned the brand as the first American-made premium beer. “The one beer to have when you’re having more than one” positioned Schaefer as the brand for the heavy beer drinker.

But there’s an imported beer whose positioning strategy is so crystal clear that those old-time beer copywriters probably wouldn’t even accept it as advertising.

“You’ve tasted the German beer that’s the most popular in America. Now taste the German beer that’s the most popular in Germany.” This is how Beck’s beer is effectively positioning itself against Lowenbrau.

Then there’s Seven-Up’s “Un-Cola” campaign.

And Sports Illustrated’s “Third Newsweekly” program.

All of these positioning campaigns have a number of things in common. They don’t emphasize product features, customer benefits or the company’s image. Yet, they are all highly successful.

Like any new concept, positioning isn’t new. At least not in the literal sense. What is new is the broader meaning now being given to the word.

Yesterday, positioning was used in a narrow sense to mean what the advertiser did to his product. Today, positioning is used in a broader sense to mean what the advertising does for the product in the prospect’s mind. In other words, a successful advertiser today uses advertising to position his product, not to communicate its advantages or feature.

Positioning has it roots in the packaged goods field where the concept was called “product positioning.” It literally meant the product’s form, package size and price as compared to competition.

Procter & Gamble carried the idea one step forward by developing a master copy platform that related each of their competing brands. For example: Tide makes clothes “white.” Cheer makes them “whiter than white.” And Bold makes them “bright.”

Although the advertising for each Procter & Gamble brand might vary from year to year, it never departed from its pre-assigned role or “position” in the master plan.

The big breakthrough came when people started thinking of positioning not as something the client does before the advertising is prepared, but as the very objective of the advertising itself. External, rather than internal, positioning.

A classic example of looking through the wrong end of the telescope was Ford’s introduction of the Edsel. In the ensuing laughter that followed, most people missed the point.

In essence, the Ford people got switched around. The Edsel was a beautiful case of internal positioning to fill a hole between Ford and Mercury on the one hand, and Lincoln on the other. Good strategy inside the building. Bad strategy outside where there was simply no position for this car in a category already cluttered with heavily chromed, medium-priced cars.

If the Edsel had been tagged a “high performance” car and presented in a sleek two-door, bucket-seat form and given a name to match, no one would have laughed. It could have occupied a position that no one else owned and the ending of the story might have been different.

To better understand what an advertiser is up against, it may be helpful to take a closer look at the objective of all advertising programs — the human mind.

Like a memory bank, the mind has a slot or “position” for each bit of information it has chosen to retain. In operation, the mind is a lot like a computer.

But there is one important difference. A computer has to accept what is put into it. The mind does not. In fact, it’s quite the opposite.

The mind, as a defense mechanism against the volume of today’s communications, screens and rejects much of the information offered it. In general, the mind accepts only that new information which matches its prior knowledge or experience. It filters out everything else.

For example, when a viewer sees a television commercial that says, “NCR means computers,” he doesn’t accept it. IBM means computers. NCR means National Cash Register.

The computer “position” in the minds of most people is filled by a company called the International Business Machines Corp. For a competitive computer manufacturer to obtain a favorable position in the prospect’s mind, he must somehow relate his company to IBM’s position.

Yet, too many companies embark on marketing and advertising programs as if the competitor’s position did not exist. They advertise their products in a vacuum and are disappointed when their messages fail to get through.

The mind, as a container for ideas, is totally unsuited to the job at hand.

There are more than 500,000 trademarks registered with the U.S. Patent Office. In addition, untold thousands of unregistered trademarks are in use throughout the country.

During the course of a single year, the average mind is exposed to more than half a million advertising messages.

The target of all this communications ammunition has a reading vocabulary of no more than 25,000 to 50,000 words, and a speaking vocabulary of one-fifth as much.

Another limitation: The average human mind, according to Harvard psychologist George A. Miller, cannot deal with more than seven units at a time. (The eighth company in a given field is out of luck.)

Ask someone to name all the brands he or she remembers in a given product category. Rarely will anyone name more than seven. And that’s for a high-interest category. For low-interest products, the average consumer can usually name no more than one or two brands.

Yet in category after category, the number of individual brands multiply like rabbits. In 1964, there were seven soft drinks advertised on network television. Today there are 22.

To cope with complexity, people have learned to reduce everything to its utmost simplicity.

When asked to describe an offspring’s intellectual progress, a person doesn’t usually quote vocabulary statistics, reading comprehension, mathematical ability, etc. “He’s in seventh grade” is a typical reply.

This “ranking” of people, objects and brands is not only a convenient method of organizing things, but also an absolute necessity if a person is to keep from being overwhelmed by the complexities of life.

You see ranking concepts at work among movies, restaurants, business and military organizations. (Some day someone might even come up with a rating system for politicians.)

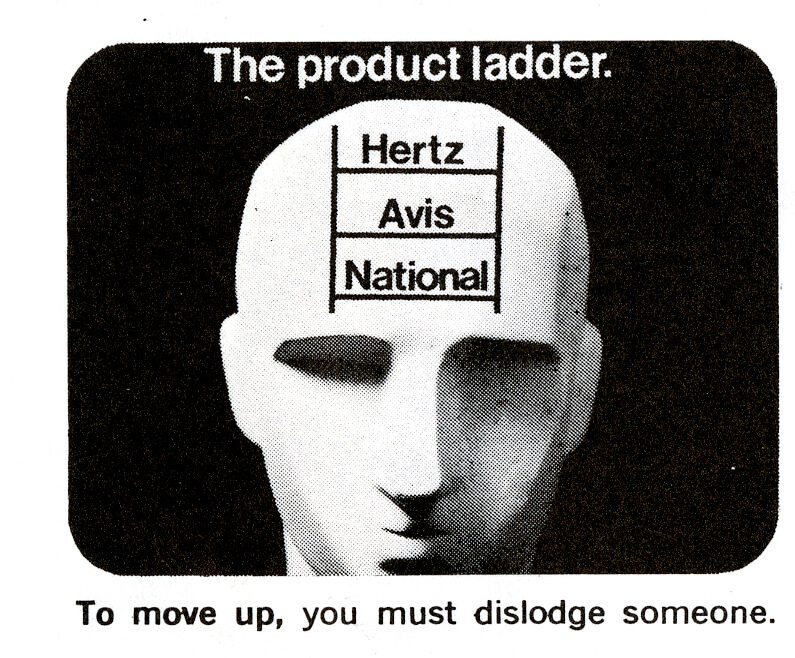

To cope with advertising’s complexity, people have learned to rank products and brands in the mind. Perhaps this can best be visualized by imagining a series of ladders in the mind. On each step is a brand name. And each different ladder represents a different product category.

Some ladders have many steps. (Seven is many.) Others have few, if any.

For an advertiser to increase his brand preference, he must move up the ladder. This can be difficult if the brands above have a strong foothold and no leverage or positioning strategy is applied against them.

For an advertiser to introduce a new product category, he must carry in a new ladder. This, too, is difficult, especially if the new category is not positioned against an old one. The mind has no room for the new and different unless it’s related to the old.

That’s why if you have a truly new product, it’s often better to tell the prospect what the product is not, rather than what it is.

The first automobile, for example, was called a “horseless” carriage, a name which allowed the public to position the concept against the existing mode of transportation.

Words like “off-track” betting, “lead-free” gasoline and “tubeless” tire are all examples of how new concepts can best be positioned against the old.

Names that do not contain an element of positioning usually die out. The “Astrojet” name dreamed up by the American Airlines is an example of a glamorous, but unsuccessful name, because it lacks a positioning idea.

The weather forecast for the old, traditional ways of advertising is gloomy at best. And nowhere was this more clearly demonstrated than in the recent Atlanta study conducted by Daniel Starch & Staff.

According to Starch, about 25% of those noting a television commercial attributed it to the competition. With virtually no exceptions, high scoring commercials were the brand leaders in their category.

The also-rans didn’t fare nearly as well. A David Janssen Excedrin commercial was associated with Anacin twice as often as Excedrin. A Pristeen commercial helped F.D.S., the brand leader, more than it did Pristeen.

This shattering turn of events is certainly “positioning” at work in our over-communicated society. It appears that unless an advertisement is based on a unique idea or position, the message is often put in the mental slot reserved for the leader in the product category.

Clutter is surely part of the reason for the rise of “misidentification.” But another, even more important factor is that times have changed. Today, you cannot advertise your product in splendid isolation. Unless your advertising positions your product in relationship to its competition, your advertising is doomed to failure.

In the positioning era, “strategy” is king. It made little difference how clever the ads of RCA, General Electric and Bristol-Myers were. Or how well the layout, copy and typography were executed. Their strategy of attacking the leaders head-on was wrong.

In the context, it’s illuminating to take a look at some recent examples of rampant creativity. The Lone Ranger and REA Express, Joe Namath and Ovaltine, Ann Miller and Great American soups. Even though these programs are highly creative, their chances for success are limited because each of them lacks a strong positioning idea.

Even creativity in the form of a slogan no longer serves much of a purpose if it doesn’t position the product.

“If you got it, flaunt it” and “We must be doing something right” achieved enormous popularity without doing much for Braniff and Rheingold. And we predict that “Try it, you’ll like it” won’t do much for Alka-Seltzer.

As far as advertising is concerned, the good old days are gone forever.

As the president of a large consumer products company said recently, “Count on your fingers the number of successful new national brands introduced in the last two years. You won’t get to your pinky.”

Not that a lot of companies haven’t tried. Every supermarket is filled with shelf after shelf of “half successful” brands. The manufacturers of these me-too products cling to the hope that they can develop a brilliant advertising campaign which will lift their offspring into the winner’s circle.

Meanwhile, they hang in there with coupons, deals, point of purchase displays. But profits are hard to come by and that “brilliant” advertising campaign, even if it comes, doesn’t ever seem to turn the brand around.

No wonder management people turn skeptical when the subject of advertising comes up. And instead of looking for new ways to put the power of advertising to work, management invents schemes for reducing the cost of what they are currently doing. Witness the rise of the house agency, the media buying service, the barter deal.

The chaos in the marketplace is a reflection of the fact that advertising just doesn’t work like it used to. But old traditional ways of doing things die hard. “There’s no reason that advertising can’t do the job,” say the defenders of the status quo, “as long as the product is good, the plan is sound and the commercials are creative.”

But they overlook one big, loud reason. The marketplace itself. The noise level today is far too high. Not only the volume of advertising, but also the volume of products and brands.

To cope with this assault on his or her mind, the average consumer has run out of brain power and mental ability. And with a rising standard of living the average consumer is less and less interested in making the “best” choice. For many of today’s more affluent customers, a “satisfactory” brand is good enough.

Advertising prepared in the old, traditional ways has no hope of being successful in today’s chaotic marketplace.

In the past, advertising was prepared in isolation. That is, you studied the product and its features and then you prepared advertising which communicated to your customers and prospects the benefits of those features.

It didn’t make much difference whether the competition offered those features or not. In the traditional approach, you ignored competition and made every claim seem like a preemptive claim. Mentioning a competitive product, for example, was considered not only bad taste, but poor strategy as well.

In the positioning era, however, the rules are reversed. To establish a position, you must often not only name competitive names, but also ignore most of the old advertising rules as well.

In category after category, the prospect already knows the benefits of using the product. To climb on his product ladder, you must relate your brand to the brands already there.

In today’s marketplace, the competitor’s image is just as important as your own. Sometimes more important. An early success in the positioning era was the famous Avis campaign.

The Avis campaign will go down in marketing history as a classic example of establishing the “against” position. In the case of Avis, this was a position against the leader.

“Avis is only No. 2 in rent-a-cars, so why go with us? We try harder.”

For 13 straight years, Avis lost money. Then the admitted they were No. 2 and have made money every year since. Avis was able to make substantial gains because they recognized the position of Hertz and didn’t try to attack them head-on.

A company can sometimes be successful by accepting a position that no one else wants. For example, virtually all automobile manufactures want the public to think they make cars that are good looking. As a result, Volkswagen was able to establish a unique position for themselves. By default.

The strength of this position, of course, is that it communicates the idea of reliability in a powerful way. “The 1970 VW will stay ugly longer” was a powerful statement because it is psychologically sound. When an advertiser admits a negative, the reader is inclined to give them the positive.

A similar principle is involved in Smucker’s jams and jellies. “With a name like Smucker’s,” says the advertising, “you know it’s got to be good.”

The advantage of owning a position can be seen most clearly in the soft drink field. Three major cola brands compete in what is really not a contest. For every ten bottles of Coke, only four bottles of Pepsi and one bottle of Royal Crown are consumed.

While there may be room in the market for a No. 2 cola, the position of Royal Crown is weak. In 1970, for example, Coca-Cola’s sales increase over the previous year (168,000,000 cases) was more than Royal Crown’s entire volume (156,000,000 cases).

Obviously, Coke has a strong grip on the cola position. And there’s not much room left for the other brands. But, strange as it might seem, there might be a spot for a reverse kind of product. One of the most interesting positioning ideas is the one currently being used by Seven-Up. It’s the “Un-Cola” and it seems silly until you take a closer look.

“Wet and Wild” was a good campaign in the image era. But the “Un-Cola” is a great program in the positioning era. Sales jumped something like 10% the first year the product was positioned against the cola field. And the increases have continued.

The brilliance of this idea can only be appreciated when you comprehend the intense share of mind enjoyed by the cola category. Two out of three soft drinks consumed in the U.S. are cola drinks.

By linking the product to what’s already in the mind of the prospect, the Un-Cola position establishes Seven-Up as an alternative to a cola drink.

A somewhat similar positioning program is working in the media field. This is the “third newsweekly” concept being used by Sports Illustrated to get into the mind of the media buyer.

It obviously is an immensely successful program. But what may not be so obvious is why it works. The “third newsweekly” certainly doesn’t describe Sports Illustrated. (As the Un-Cola doesn’t describe Seven-Up.)

What it does do, however, is to relate the magazine to a media category that is uppermost in the prospect’s mind (as the Un-Cola relates to the soft drink category that is uppermost in the mind).

In order to position your own brand, it’s sometimes necessary to reposition the competitor.

In the case of Beck’s beer, the repositioning is done at the expense of Lowenbrau: “You’ve tasted the German beer that’s the most popular in America. Now taste the German beer that’s the most popular in Germany.”

This strategy works because the prospect had assumed something about Lowenbrau that wasn’t true.

The current program for Raphael aperitif wine also illustrates this point. The ads show a bottle of “made in France” Raphael and a bottle of “made in U.S.A.” Dubonnet. “For $1.00 a bottle less,” says the headline, “you can enjoy the imported one.” The shock, of course, is to find that Dubonnet is a product of the U.S.

In the positioning era, the name of a company or product is becoming more and more important. The name is the hook that allows the mind to hang the brand on its product ladder. Given a poor name, even the best brand in the world won’t be able to hang on.

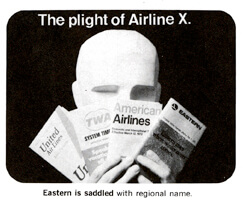

Take the airline industry. The big four domestic carriers are United, American, TWA and an airline we’ll call Airline X.

Like all airlines, Airline X has had its ups and downs. Unfortunately, there have been more downs than ups. But unlike some of its more complacent competitors, Airline X has tried. A number of years ago, it brought in big league marketing people and pushed in the throttle.

Airline X was among the first to “paint the planes,” “improve the food” and “dress up the stewardesses” in an effort to improve its reputation.

And Airline X hasn’t been bashful when it comes to spending money. Year after year, it has one of the biggest advertising budgets in the industry. Even though it advertises itself as “the second largest passenger carrier of all the airlines in the free world,” you may not have guessed that Airline X is Eastern. Right up there spending with the worldwide names.

For all that money, what do you think of Eastern? Where do you think they fly? Up and down the East Coast, to Boston, Washington, Miami, right? Well, Eastern also goes to St. Louis, New Orleans, Atlanta, San Francisco, Acapulco. But Eastern has a regional name, and their competitors have broader names which tell the prospect they fly everywhere.

Look at the problem from just one of Eastern’s cities, Indianapolis. From Indianapolis, Eastern flies north to Chicago, Milwaukee and Minneapolis. And south to Birmingham and Mobile. They just don’t happen to fly east.

And then there is the lush San Juan run which Eastern has been serving for more than 25 years. Eastern used to get the lion’s share of this market. Then early last year American Airlines took over Trans Caribbean. So today, who is number one to the San Juan sun? Why American, of course.

No matter how hard you try, you can’t hang “The Wings of Man” on a regional name. When the prospect is given a choice, he or she is going to prefer the national airline, not the regional one.

What does a company do when its name (Goodrich) is similar to the name of a much larger company in the same field (Goodyear)?Goodrich had problems. They could reinvent the wheel, and Goodyear would get most of the credit.If you watched the Super Bowl last January, you saw both Goodrich and Goodyear advertise their “American-made radial-ply tires.” But which company do you think got their money’s worth at $200,000 a pop? We haven’t seen the research, but our bet would be on Goodyear, the company that owns the tire position.

But even bad names like Eastern and Goodrich are better than no name at all.

In Fortune’s list of 500 largest industrials, there are now 16 corporate nonentities. That is, 16 major American companies have legally changed their names to meaningless initials.

How many of these companies can you recognize: ACF, AMF, AMP, ATO, CPC, ESB, FMC, GAF, NVF, NL, PPG, RCA, SCM, TRW, USM and VF?

These are not tiny companies either. The smallest of them, AMP, has more than 10,000 employees and sales of over $225,000,000 a year.

What companies like ACF, AMF, AMP and the others fail to realize is that their initials have to stand for something. A prospect must know your name first before he or she can remember your initials.

GE stands for General Electric. IBM stands for International Business Machines. And everyone knows it. But how many people knew that the ACF stood for American Car & Foundry?

Furthermore, now that ACF has legally changed its name to initials, there’s presumably no way to even expose the prospect to the original name.

An exception seems to be RCA. After all, everyone knows that RCA stands for, or rather used to stand for, Radio Corp. of America.

That may be true today. But what about tomorrow? What will people think 20 years from now when they see those strange initials. Roman Catholic Archdiocese?

And take Corn Products Co. Presumably it changed its name to CPC International because it makes products out of lots of things besides corn, but you can’t remember “CPC” without bringing Corn Products Co. to mind. The tragedy is, CPC made the change to “escape” the past. Yet the exact opposite occurred.

Names are tricky. Consider the Protein 21/29 shampoo, hair spray, conditioner, concentrate mess.

Back in 1970, the Mennen Co. introduced a combination shampoo conditioner called “Protein 21.” By moving rapidly with a $6,000,000 introductory campaign (followed by a $9,000,000 program the next year), Mennen rapidly carved out a 13% share of the $300,000,000 shampoo market.

Then Mennen hit the line extension lure. In rapid succession, the company introduced Protein 21 hairspray, Protein 29 hairspray (for men), Protein 21 conditioner (in two formulas), Protein 21 concentrate. To add to the confusion, the original Protein 21 was available in three different formulas (for dry, oily and regular hair).

Can you imagine how confused the prospect must be trying to figure out what to put on his or her head? No wonder Protein 21’s share of the shampoo market has fallen from 13% to 11%. And the decline is bound to continue.

Another similar marketing pitfall recently befell, of all companies, Miles Laboratories.

You can see how it happens. A bunch of the boys are sitting around a conference table trying to name a new cold remedy.

“I have it,” says Harry. “Let’s call it Alka-Seltzer Plus. That way we can take advantage of the $20,000,000 we’re already spending to promote the Alka-Seltzer name.”

“Good thinking, Harry,” and another money-saving idea is instantly accepted.

But lo and behold, instead of eating into the Dristan and Contac market, the new product turns around and eats into the Alka-Seltzer market.

And you know Miles must be worried. In every TV commercial, the “Alka-Seltzer” gets smaller and smaller and the “Plus” gets bigger and bigger.

Related to the free-ride trap, but not exactly the same, is another common error of judgment called the “well-known name” trap.

Both General Electric and RCA thought they could take their strong positions against IBM in computers. But just because a company is well known in one field doesn’t mean it can transfer that recognition to another.

In other words, your brand can be on top of one ladder and nowhere on another. And the further apart the products are conceptually, the greater the difficulty of making the jump.

In the past when there were fewer companies and fewer products, a well-known name was a much greater asset than it is today. Because of the noise level, a “well-known” company has tremendous difficulty trying to establish a position in a different field than the one in which it built its reputation.

A human emotion called “greed” often leads an advertiser into another error. American Motors’ introduction of the Hornet is one of the best examples of the “everybody” trap.

You might remember the ads, “The little rich car. American Motors Hornet: $1,994 to $3,589.”

A product that tries to appeal to everybody winds up appealing to no one. People who want to spend $3,500 for a car don’t buy the Hornet because they don’t want their friends to think they’re driving a $1,900 car. People who want to spend $1,900 for a car don’t want a car with $1,600 worth of accessories taken off of it.

If the current Avis advertising is any indication, the company has forgotten what made them successful.

The original campaign not only related No. 2 Avis to No. 1 Hertz, but also exploited the love that people have for the underdog. The new campaign (Avis is going to be No. 1) not only is conventional “brag and boast” advertising but also dares the prospect to make the prediction not come true.

Our prediction: Avis ain’t going to be No. 1. Further prediction: Avis will lose ground to Hertz and National.

Another company that seems to have fallen into the forgotten-what-made-them-successful trap is Volkswagen.

“Think small” was perhaps the most famous advertisement of the ‘60s. Yet last year VW ran an ad that said, “Volkswagen introduces a new kind of Volkswagen. Big.”

O.K., Volkswagen, should we think small or should we think big?

Confusion is the enemy of successful positioning. Prediction: Rapid erosion of the Beetle’s position in the U.S. market.

Years ago, a successful product might live 50 years or more before fading away. Today, a product’s life cycle is much shorter. Sometimes it can be measured in months instead of years.

New products, new services, new markets, even new media are constantly being born. They grow up into adulthood and then slide into oblivion. And a new cycle starts again.

Yesterday, beer and hard liquor were campus favorites. Today it’s wine.

Yesterday, the well-groomed man has his hair cut every week. Today, it’s every month or two.

Yesterday, the way to reach the masses was the mass magazines. Today, it’s network TV. Tomorrow, it could be cable.

The only permanent thing in life today is change. And the successful companies of tomorrow will be those companies that have learned to cope with it.

The acceleration of “change” created enormous pressures on companies to think in terms of tactics rather than strategy. As one respected advertising man commented, “The day seems to be past when long-range strategy can be a winning technique.”

But is change the way to keep pace with change? The exact opposite appears to be true.

The landscape is littered with the debris of projects that companies rushed into in attempting to “keep pace.” Singer trying to move into the boom in home appliances. RCA moving into the boom in computers. General Foods moving into the boom in fast-food outlets. Not to mention the hundreds of companies that threw away their corporate identities to chase the passing fad to initials.

While the programs of those who kept at what they did best and held their ground have been immensely successful. Maytag selling their reliable appliances. Walt Disney selling his world of fantasy and fun. Avon calling.

And take margarine. Thirty years ago the first successful margarine brands positioned themselves against butter. “Tastes like the high-priced spread,” said a typical ad.

And what works today? Why the same strategy. “It isn’t nice to fool Mother Nature,” says the Chiffon commercial, and sales go up 25%. Chiffon is once again the best selling brand of soft margarine.

Change is a wave on the ocean of time. Short term, the waves cause agitation and confusion, but long term the underlying currents are much more significant.

To cope with change, it’s important to take a long-range point of view. To determine your basic business. Positioning is a concept that is cumulative. Something that takes advantage of advertising’s long-range nature.

In the ‘70’s, a company must think even more strategically than it did before. Changing the direction of a large company is like trying to turn an aircraft carrier. It takes a mile before anything happens. And if it was a wrong turn, getting back on course takes even longer.

To play the game successfully, you must make decisions on what your company will be doing not next month or next year, but in five years, ten years. In other words, instead of turning the wheel to meet each fresh wave, a company must point itself in the right direction.

You must have vision. There’s no sense building a position based on a technology that’s too narrow. Or a product that’s becoming obsolete. Remember the famous “Harvard Business Review” article entitled “Marketing Myopia”? It still applies.

If a company has positioned itself in the right direction, it will be able to ride the currents of change, ready to take advantage of those opportunities that are right for it. But when an opportunity arrives, a company must be ready to move quickly.

Because of the enormous advantages that accrue to being the leader, most companies are not interested in learning how to compete with the leader. They want to be the leader. They want to be Hertz rather than Avis. Time rather than Newsweek. General Electric rather than Westinghouse.

Historically, however, product leadership is usually the result of an accident, rather than a preconceived plan.

The xerography process, for example, was offered to 32 different companies (including IBM and Kodak) before it wound up at the Haloid Co. Renamed Haloid Xerox and then finally Xerox, the company has since dominated the copier market. Xerox now owns the copier position.

Were IBM and Kodak stupid to turn down xerography? Of course not. These companies reject thousands of ideas every year.

Perhaps a better description of the situation at the time was that Haloid, a small manufacturer of photographic supplies, was desperate, and the others weren’t. As a result, it took a chance that more prudent companies couldn’t be expected to take.

When you trace the history of how leadership positions were established, from Hershey in chocolate to Hertz in rent-a-cars, the common thread is not marketing skill or even product innovation. The common thread is seizing the initiative before the competitor has a chance to get established. In someone’s old-time military terms, the marketing leader “got there firstest with the mostest.” The leader usually poured in the marketing money while the situation was still fluid.

IBM, for example, didn’t invent the computer. Sperry Rand did. But IBM owns the computer position because they built their computer fortress before competition arrived.

And the position that Hershey established in chocolate was so strong they didn’t need to advertise at all, a luxury that competitors like Nestle couldn’t afford.

You can see that establishing a leadership position depends not only on luck and timing, but also upon a willingness to “pour it on” when others stand back and wait.

Yet all too often, the product leader makes the fatal mistake of attributing its success to marketing skill. As a result, it thinks it can transfer that skill to other products and other marketing situations.

Witness, for example, the sorry record of Xerox in computers. In May of 1969, Xerox exchanged nearly 10,000,000 shares of stock (worth nearly a billion dollars) for Scientific Data Systems Inc. Since the acquisition, the company (renamed Xerox Data Systems) has lost millions of dollars, and without Xerox’s support would have probably gone bankrupt.

And the mecca of marketing knowledge, International Business Machines Corp., hasn’t done much better. So far the IBM plain-paper copier hasn’t made much of a dent in Xerox’s business. Touché.

The rules of positioning hold for all types of products. In the packaged goods area, for example, Bristol-Myers tried to take on Crest toothpaste with Fact (killed after $5,000,000 was spent on promotion). Then they tried to go after Alka-Seltzer with Resolve (killed after $11,000,000 was spent). And according to a headline in the Feb. 7 issue of Advertising Age, “Bristol-Myers will test Dissolve aspirin in an attempt to unseat Bayer.”

The suicidal bent of companies that go head-on against established competition is hard to understand. They know the score, yet they forge ahead anyway. In the marketing war, a “charge of the light brigade” happens every day. With the same predictable result.

Successful marketing strategy usually consists of keeping your eyes open to possibilities and then striking before the product ladder is firmly fixed.

As a matter of fact, the marketing leader is usually the one who moves the ladder into the mind with his or her brand nailed to the one and only rung. Once there, what can a company do to keep its top-dog position?

There are two basic strategies that should be used hand in hand. They seem contradictory, but aren’t. One is to ignore competition, and the other is to cover all bets.

As long as a company owns the position, there’s no point in running ads that scream, “We’re No. 1.” Much better is to enhance the product category in the prospect’s mind. Notice the current IBM campaign that ignores competition and sells the value of computers. All computers, not just the company’s types.

Although the leader’s advertising should ignore the competition, the leader shouldn’t. The second rule is to cover all bets.

This mean a leader should swallow his or her pride and adopt every new product development as soon as it shows sign of promise. Too often, however, the leader pooh-poohs the development, and doesn’t wake up until it’s too late.

Most companies are in the No. 2, 3, 4 or even worse category. What then?

Hope springs eternal in the human breast. Nine times out of ten, the also-ran sets out to attack the leader a la RCA’s assault on IBM. Result: Disaster.

Simply stated, the first rule of positioning is this: You can’t compete head-on against a company that has a strong, established position. You can go around, under or over, but never head-to-head.

The leader owns the high ground. The No. 1 position in the prospect’s mind. The top rung of the product ladder.

The classic example of No. 2 strategy is Avis. But many marketing people misread the Avis story. They assume the company was successful because it tried harder.

Not at all. Avis was successful because it related itself to the position of Hertz. Avis preempted the No. 2 position. (If trying harder were the secret of success, Harold Stassen would be president.)

Most marketplaces have room for a strong No. 2 company provided they position themselves clearly as an alternative to the leader. In the computer field, for example, Honeywell has used this strategy successfully.

“The other computer company vs. Mr. Big,” says a typical Honeywell ad. Honeywell is doing what none of the other computer companies seems to be willing to do. Admit that IBM is, in fact, the leader in the computer business. Maybe that’s why Honeywell and Mr. Big are the only large companies reported to be making money on computers.

Yet there are positions that can be taken. These are positions that look strong, but in reality are weak.

Take the position of Scott in paper products. Scott has about 40% of the $1.2 billion market for towels, napkins, toilet tissues and other consumer paper products. But Scott, like Mennen with Protein 21, fell into the line-extension trap.

ScotTowels, ScotTissue, Scotties, Scottkins, even BabyScott. All of these names undermined the Scott foundation. The more products hung on the Scott name, the less meaning the name had to the average consumer.

When Procter & Gamble attacked with Mr. Whipple and his tissue-squeezers, it was no contest. Charmin in now the No. 1 brand in the toilet-tissue market.

In Scott’s case, a large “share of market” didn’t mean they owned the position. More important is a large “share of mind.” The housewife could write “Charmin, Kleenex, Bounty and Pampers” on her shopping list and know exactly what products she was going to get. “Scott” on a shopping list has no meaning. The actual brand names aren’t much help either. Which brand, for example, is engineered for the nose, Scotties or ScotTissue?

In positioning terms, the name “Scott” exists in limbo. It isn’t firmly ensconced on any product ladder.

To repeat, the name is the hook that hangs the brand on the product ladder in the prospect’s mind. In the positioning era, the brand name to give a product is probably a company’s single most important marketing decision.

To be successful in the positioning era, advertising and marketing people must be brutally frank. They must try to eliminate all ego from the decision-making process. It only clouds the issue.

One of the most critical aspects of “positioning” is being able to evaluate objectively products and how they are viewed by customers and prospects.

As a rule, when it comes to building strong programs, trust no one, especially managers who are all wrapped up in their products. The closer people get to products, the more they defend old decisions or old promises.

Successful companies get their information from the marketplace. That’s the place where the program has to succeed, not in the product manager’s office.

A company that keeps its eye on Tom, Dick and Harry is going to miss Pierre, Hans and Yoshio.

Marketing is rapidly becoming a worldwide ballgame. A company that owns a position in one country now finds that it can use the position to wedge its way into another.

IBM has 62% of the German computer market. Is this fact surprising? It shouldn’t be. IBM earns more than 50% of its profits outside the U.S.

As companies start to operate on a worldwide basis, they often discover they have a name problem.

A typical example is U.S. Rubber, a worldwide company that marketed many products not made of rubber. Changing the name to Uniroyal created a new corporate identity that could be used worldwide.

In the ‘70s, creativity will have to take a back seat to strategy.

Advertising Age itself reflects this fact. Today you find fewer stories about individual campaigns and more stories about what’s happening in an entire industry. Creativity alone isn’t a worthwhile objective in an era where a company can spend millions of dollars on great advertising and still fail miserably in the marketplace.

Consider what Harry McMahan calls the “Curse of Clio.” In the past, the American Festival has made special awards to “Hall of Fame Classics.” Of the 41 agencies that won these Clio awards, 31 have lost some or all of these particular accounts.

But the cult of creativity dies hard. One agency president said recently, “Oh, we do positioning all the time. But after we develop the position, we turn it over to the creative department.” And too often, of course, the creativity does nothing but obscure the positioning.

In the positioning era, the key to success is to run naked positioning statements, unadorned by so-called creativity.

If these examples have moved you to want to apply positioning thinking to your own company’s situation, here are some questions to ask yourself:

Get the answer to this question from the marketplace, not the marketing manager. If this requires a few dollars for research, so be it. Spend the money. It’s better to know exactly what you’re up against now than to discover it later when nothing can be done about it.

Here is where you bring out your crystal ball and try to figure out the best position to own from a long-term point of view.

If your proposed position calls for a head-to-head approach against a marketing leader, forget it. It’s better to go around an obstacle rather than over it. Back up. Try to select a position that no one else has a firm grip on.

A big obstacle to successful positioning is attempting to achieve the impossible. It takes money to build a share of mind. It takes money to establish a position. It takes money to hold a position once you’ve established it.The noise level today is fierce. There are just too many “me-too” products and too many “me-too” companies vying for the mind of the prospect. Getting noticed is getting tougher.

With the noise level out there, a company has to be bold enough and consistent enough to cut through.The first step in a positioning program normally entails running fewer programs, but stronger ones. This sounds simple, but actually runs counter to what usually happens as corporations get larger. They normally run more programs, but weaker ones. It’s this fragmentation that can make many large advertising budgets just about invisible in today’s media storm.

Creative people often resist positioning thinking because they believe it restricts their creativity. And it does. But creativity isn’t the objective in the ‘70s. Even “communications” itself isn’t the objective.The name of the marketing game in the ‘70s is “positioning.” And only the better players will survive.