The Sad Saga of Sears

With the Kmart marriage going bad, employees jumping ship and a patriarch who doesn’t appear to know what he is doing, Sears is falling apart. Sears’ shares, which reached a high of $195.18 in April, fell to $98.49 on Monday as news broke that Aylwin Lewis, its president and chief executive, would step down.

With 3,800 Sears and Kmart stores, the company is still the fourth largest retailer in the U.S., but its future looks gloomy with many analysts suggesting they sell off the remaining assets for scrap.

How did it all go wrong? It is not such a mystery. A quick look at history explains the downfall of this American icon.

During the last century, Sears, Roebuck and Co. was the gold standard in the industry. Sears was the biggest, most profitable retailer in America. Hard to believe now, especially if you were born after 1985, but it is true. Sears was the “it” company of its day. The public, investors and Wall Street thought it could do no wrong.

The beginning of the end usually starts with that kind of thinking. When you think you can do anything with your brand, it all starts to fall apart.

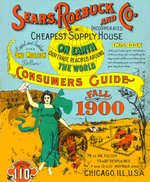

Sears began as a mail-order catalog business back in the late 1800’s targeting primarily farmers. In 1925, the first retail store was opened and success came quickly. In particular, the Sears store-branded merchandise was a hit. After WW II things really took off. Sales hit $1 billion dollars in 1945 and doubled just a year later.

As the early explosive growth of a category slows (and it always does), a company usually tries expansion to compensate. This is the fatal flaw.

As sales of its core durable goods started to fall off, Sears started stocking more clothing to compensate. And so began the beginning of the end.

In the 1980s with sales continuing to slide, Sears sought expansion through diversification. Sears bought real estate company Coldwell Banker and stock brokerage firm Dean Witter Reynolds. Sears also launched the Discover credit card.

The purchases culminated in the now infamous “stocks to socks strategy.” Brilliant! You can buy your socks, your stocks, your real estate, your daughter’s prom dress all at Sears. Did it work? Of course not.

Expansion might help in the short term, but in the long term expansion a company unfocused. And an unfocused company stuck in the mushy middle of its category is ripe picking for competition. As an industry matures, competitors come in and steal market share from above you as well as below you. This is exactly what happened to Sears.

While Sears stayed in the middle of the department-store market, the department-store industry was diverging into two separate industries, one at the low end and one at the high end.

At the low end, Wal-Mart and Target have become big money-makers. Target has almost twice the revenues of Sears and Wal-Mart has more than 10 times the revenues. In 2006, Sears did $30.0 billion in sales while Target did $59.5 billion and Wal-Mart did an incredible $348.7 billion.

At the high end, retailers like Nordstrom and Saks Fifth Avenue are doing well as are a host of high-end boutiques.

What should Sears have done? Management-school logic would suggest that Sears, Roebuck and Co. should have either moved upscale or downscale in the department-store industry. But that’s not sound marketing logic.

Marketing logic states that once you have a strong position in the mind, you can’t change it. Therefore, the marketing answer to every problem is always the same.

Focus.

When faced with a broadening of its category, Sears should have narrowed its focus and become a specialist. Instead of shifting to the softer side of Sears, the retailer should have further embraced its harder side.

The harder side is where Sears was the strongest and had the most credibility anyway. Sears was once America’s leading seller of major appliances with 41 percent of the market. That share is steadily eroding as Lowe’s, Home Depot and Best Buy take appliance business away from Sears.

The mistakes of Sears have been compounding for decades. The company kept expanding into softer goods when they should have been focusing on harder goods.

Instead of advancing into its weakness (clothing and soft goods) by buying Lands End for $1.9 billion, Sears should have been retreating to its strength in hard goods and bought Black & Decker.

And let’s not forget, Sears has some of the strongest hard-good brands in the industry like Kenmore, Craftsman and DieHard. These brands could have crowned Sears as the hard goods king and blocked much of the progress Home Depot has been able to make.

But I think the final straw for Sears was Eddie Lampert’s unwise take-over. High-flying hedge-fund legend, Eddie Lampert acquired Kmart in 2003 and Sears in 2005. Combining the two struggling retailers was suppose to deliver synergy but instead brought misery.

Combining two losers doesn’t make a winner. It just doubles your problems. Sears and its owner Eddie Lampert whose fund holds 48% of the company are in deep trouble.

Eddie Lampert, a man who was once called the Warren Buffet of his generation, may have ruled out that comparison for good.

Lampert’s rise and current fall are emblematic of the recent trend of having money managers buy and run companies. The implication is that great value can be created by simply managing assets better. But nothing could be further from the truth. Managing assets usually translates into going over expenses and looking for ways to cut costs. And while saving money and cutting waste are good, those steps alone don’t make a company powerful.

What makes a company powerful? Size, strength, stock price? None of these.

What makes a company powerful is owning powerful brands. Powerful brands are brands that are singular, dominant and in growing categories.

Today, neither Sears nor Kmart are powerful brands. Bad news for Lampert and his legacy.

Warren Buffet is famous for buying the right brands on their way up. Lampert will unfortunately be known for buying the wrong brands on their way down.

?>

?>